0.The Legend of Loreley

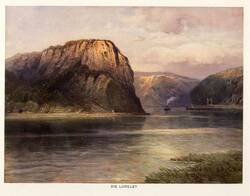

The Loreley rock (also spelled Lorelei) is located in the Upper Middle Rhine Valley near Sankt Goarshausen in Germany. The valley was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002. The steep slate rock watches over a part of the river Rhine that is considered very dangerous because of its narrow bends and rocky ground. To this day, ships are being guided by light signals to avoid accidents. From a viewing platform on top of the rock, visitors can look over the river curve and see the sister towns Sankt Goar and Sankt Goarshausen as well as the castles Katz and Rheinfels. A few hundred metres away from the platform there is an open-air stage called Freilichtbühne Loreley.[Anm. 1]

0.1.The Loreley rock before the legend

People have populated the surrounding area of the rock since the Old Stone Age (Palaeolithic). In the Middle Ages, small villages developed from Roman settlements. [Anm. 2]The town of Sankt Goar was visited by very early tourists because sailors were advised to visit its church to thank the patron saint St Goar of Aquitaine for having braved the dangerous part of the river. [Anm. 3]

The rock inspired various local legends because it produced a strong echo effect. Around the year 1500 poet and humanist Konrad Celtes reported forest spirits or dwarves living in caves in the rock who caused the mysterious echo. Dwarves, who were sometimes called “Luren”, were said to protect precious objects – and so some people believed this was the location of a legendary hidden treasure known from the Nibelungenlied, an epic poem written in Germany around 1200. [Anm. 4] In 1612 Marquard Friedrich Freher wrote the rock was home to forest or mountain nymphs; the most famous of the latter is indeed a nymph called Echo whose tale is told in Greek mythology.

We see that so far Loreley only was the name of the rock and the echo. There were legends surrounding it, but the phenomenon had not yet been attributed to a single person or entity.[Anm. 5]

Etymologists are not sure where and how the name Loreley originated. In earlier times, the rock was also called “Lurlaberch”, “Lurley” or “Lureley”. Up until the 19th century the name had a male German article – this probably changed when the legends of the female siren Loreley emerged. “Ley” is a celtic word meaning rock and it was also used in German dialects of the area. [Anm. 6]“Lur” seems to have various different meanings – it could mean “loud”, or “to lurk”, or be referring to the aforementioned “Luren”, meaning dwarves and elves. This would mean Loreley rock could be translated to elven rock. [Anm. 7] The first to use the name Loreley to describe a woman was German author Clemens Brentano, whose first poem including a character called Lore Lay was published in 1801 in his book Godwi oder Das steinerne Bild der Mutter. [Anm. 8]

0.2.Conception of the literary character Loreley

Clemens Brentano (1778-1842) was an author of the German Romanticist movement in late 18th and 19th century. Common features of works from this period were high emphasis on describing emotions, nature and a strong inclination towards fairy tales and magical themes. For sake of the stories, historical inaccuracy as well as complete distortion of reality was tolerated.

In Brentano’s romantic ballad, Lore Lay is a beautiful woman adored by many men. She is said to be causing their deaths by bewitching them and is brought before a bishop. She explains that she is suffering from unrequited love for a man who will not return to her and therefore wishes to die. Instead of convicting her for using magic, the bishop too is enchanted by her beauty and sends her to a nunnery to atone for her sins. On the way there Lore Lay and the three knights guarding her pass the rock by the river Rhine. Lore Lay asks to climb it one last time to watch out for her unfaithful lover, believes to spot him on a ship and falls to her death. The knights follow her, and so her name has been echoing from the rock ever since.

Perhaps Brentano based his poem on the ancient myth of the nymph Echo, who herself turned into a rock echoing her name because of grief about her unrequited love for Narcissus. This way Brentano created an explanation for the echo effect around the Rhine rock that could easily be retold. Of course people in his time were fully aware that the poem was not in fact an explanation for the echo – however the tale seemed so plausible, that it could very well have been an attempt at explaining the phenomenon from a time without any science. Soon Brentano’s poem was being spread as a re-narration of a supposedly ancient legend.

0.3.Distribution and development of the supposed folk tale

In 1811 historian Niklas Vogt described the echo of the Loreley rock as the voice of a woman who had died as described in Brentano’s ballad (he only corrected this years later, when he came to the conclusion that Brentano must have made the tale up).[Anm. 9] Another historian and teacher called Alois Schreiber published a traveller’s guide called Handbuch für Reisende am Rhein in 1812. The book featured old legends surrounding the river Rhine, among which – misleadingly – a narration of Brentano’s poem. The guide was particularly popular among British tourist and largely influenced the popularity of the Rhine and its romanticization (“Rheinromantik”).[Anm. 10]

In the poem Waldgespräch (“forest dialogue“) by German poet Joseph von Eichendorff from 1815, Lorelei is a witch who owns a castle by the river Rhine. She curses her (male) victims to get lost in the forest and thus die, her motive being a broken heart. Another poet called Otto Heinrich Graf von Loeben wrote Der Lurleyfels (“the Lurley rock”) in 1821 and made Loreley a murderous siren sitting on a rock by the Rhine and distracting doomed sailors with enchanting songs.[Anm. 11]

0.4.Popularity through Heinrich Heine

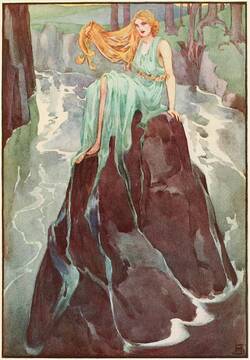

Influenced by all aforementioned versions of the same story, German author Heinrich Heine published his interpretation in the form of a rather melancholic untitled poem in 1823. Here Loreley is an enchantingly beautiful, siren-like woman luring sailors to their death in the dangerous rocks by singing to them. She is described as having golden hair shimmering in moonlight – a scene often depicted by various painters. Because the name Loreley (spelled Lore-Ley) is only mentioned in the very last verse, we can gather that the tale must have been so popular that Heine could rely on everyone already being familiar with it. He too refers to the story as a “fairy tale from old times” and hereby pretends to only have written down what people had verbally retold until then, which is how the Brothers Grimm were collecting their fairy tales around the same time.[Anm. 12]

Heine’s poem has been set to music over 40 times, among others by Robert Schumann, but the most popular version became a piece by Friedrich Silcher from 1837. Through music Heine’s poem reached even more people: The song quickly became a folk song. Many did not know who actually wrote the text, and perhaps it would not have reached its popularity had it not been for Silcher’s melody because Heine was a very controversial person in German society at the time.[Anm. 13]

Nevertheless, Heine’s poem and Silcher’s music became hugely popular in Germany. German patriotism and “Rheinromantik” were fuelled by wars against France, the Rhine was perceived as the natural border between Germans and France that must be protected at all costs. This nationalistic mood gave birth to texts such as Die Wacht am Rhein (“the watch by the Rhine”) by Max Schneckenburger (1840), which again became hugely popular in 1870/71 when Otto von Bismarck (Chancellor of the German Empire from 1871 to 1890) was waging war against France. Because the river was being associated with patriotism (and nationalism) so early on, Loreley too was seen as a personification of German virtues.[Anm. 14]

Heine himself was very critical of patriotism and even more so of nationalism. The author, who was born in 1797 from Jewish descent, was in favour of cosmopolitanism and wanted people to engage regardless of their place of birth and social status. Being ahead of their time, most of his works were censored by the German Confederation. In 1831 Heine moved to exile in Paris, which is why many Germans thought of him as a traitor for renouncing or even hating his native country. He died in 1856 but public debates about his literary afterlife continued for a long time.[Anm. 15]

In 1905/06 journalist Richard A. Bermann described the paradoxical public opinion of Heine by writing, “You spit on him, wipe your mouth and whistle his Loreley-song”.[Anm. 16] Unsurprisingly the “Third Reich” tried to hush up the fact that Jewish Heine was author of the text of the song.[Anm. 17] They claimed that musicians such as Silcher, Schumann or Schubert, who other than that were “exemplary Arian”, had only used his text for their music because they had interpreted Heine’s text differently – meaning more patriotic, more Germany-loving – than Heine originally had intended.[Anm. 18] Obviously this judgement was based on anti-Semitism, however it is true that Heine’s goals was by far not to make Loreley a symbol for anything, let alone nationalism that he despised. Because his poem had reached such a great level of popularity, it had become something else. Literary scientist Paula Wojcik described this process as an object of high cultural, artistic value becoming a mere element of mass entertainment.[Anm. 19]

0.5.International response and development until today

Had early entrepreneurs not seen the potential of the national sight in combination with the popular story, it might not have become as famous. Starting 1853, a shipping company based in Cologne and Düsseldorf offered trips on steamboats for tourists. They even payed someone to produce the famous echo effect by shooting pistols and sounding a bugle in the rock’s caves.[Anm. 20]

Especially in the USA the Loreley legend was very popular. Mark Twain travelled Germany and Switzerland in 1878/79 and published a report called A Tramp Abroad a year later. He referred to Loreley as an “ancient legend of the Rhine” and included Heine’s poem as well as the sheet music to Silcher’s song and a translation in the book.[Anm. 21]

Alfred J. Pearson, who was professor of English and German at Drake University, Iowa, visited the rock in course of the American occupation of the Rhineland after the First World War. He too dedicated a chapter of his book The Rhine and its Legends to Loreley but (overall rather unimpressed with the sight) pointed out that the tale was a mere invention of Brentano.[Anm. 22]

In the famous film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes from 1953, Marylin Monroe played a blonde temptress called Lorelei Lee.

During the “Third Reich” the National Socialists built a so-called “Thingstätte” at the Loreley rock – an outdoor amphitheatre for political and artistic performances meant to unite people and strengthen National Socialist values. When the American army came into the region in 1945, they put up their flag to symbolically announce the occupation of the Rhineland. They did not destroy the amphitheatre so that it could be used as an open-air stage for theatre productions by director Karl Siebold until the 1950’s. Since 1976 the venue has been used for rock and pop concerts that are being hosted by Loreley Venue Management GmbH since 2010.[Anm. 23] In 2000 the Loreley visitors’ centre opened with a museum.

Summarizing, the legend of the Loreley is an entirely made up story. Clemens Brentano invented it as an origin myth (also called etiological myth or aition) to explain the echo effect of the Loreley rock, and many authors since picked up the idea. The nature of the character Loreley too changed from a woman unhappily in love to a deliberate murderer and femme fatale. By the end of the 19th century the tale of the Rhine siren was so widely spread that people believed it to be an actual legend that so far had only been told verbally. To this day many assume this to be true.

0.6.References

Author: Katrin Kober

Published: 2020-05-18

Bib Bibliography:·

- Alfred John Pearson. In: Drakeapedia, 2018-06-01. URL: https://drakeapedia.library.drake.edu/w/index.php?title=Alfred_John_Pearson&oldid=25076 (Retrieved 2020-04-20).

- Benner, Iris: Review of: Mario Kramp/Matthias Schmandt (Pub.): Die Loreley. Ein Fels am Rhein. Ein deutscher Traum, Mainz 2004. In: sehepunkte 5 (2005), Nr. 6, URL: http://www.sehepunkte.historicum.net/2005/06/7615.html (Retrieved 2020-04-03).

- Dieterle, Bernard: Der Rhein. Landschaft, Kultur, Literatur. In: KulturPoetik 1, Vol. 1 (2001), p. 96-113, URL: www.jstor.org/stable/40621625 (Retrieved 2020-04-02).

- Dirsch, Felix: Loreley, 25.10.2016, https://wiki.staatspolitik.de/index.php?title=Loreley (Retrieved 2020-04-03).

- Feuerlicht, Ignaz: Heine’s “Lorelei“. Legend, Literature, Life. In: The German Quarterly 53, Vol. 1 (1980), p. 82-94, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/405246 (Retrieved 2020-04-02).

- Galley, Eberhard: Heine, Heinrich. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 8 (1969), p. 286-291, https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118548018.html#ndbcontent (Retrieved 2020-04-14).

- Karst, Theodor: „Ich weiss nicht, was soll es bedeuten“. Heines Loreley-Gedicht und seine Vorläufer im Unterricht. In: Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German 1, Vol. 2 (1968), p. 36–53, URL: www.jstor.org/stable/3529041 (Retrieved 2020-04-03).

- Kiewitz, Susanne: Review of: Mario Kramp/Matthias Schmandt (Pub.): Die Loreley. Ein Fels am Rhein. Ein deutscher Traum, Mainz 2004. In: H-Soz-Kult 22.08.2005, URL: https://www.hsozkult.de/publicationreview/id/reb-6685 (Retrieved 2020-04-03).

- Kluckhohn, Paul: Brentano, Clemens. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie 2 (1955), p. 589-593 [online version]; URL: www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118515055.html (Retrieved 2020-04-08).

- Pearson, Alfred J.: The Rhine and its Legends. A Souvenir of the Days of the American Army of Occupation in Germany, Koblenz 1919, URL: https://www.dilibri.de/rlb/content/titleinfo/181562?query=the%20rhine%20and%20its%20legend (Retrieved 2020-04-20).

- Philippson, Ernst A.: Über das Verhältnis von Sage und Literatur. In: PMLA 62, Vol. 1 (1947), p. 239-261, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/459203 (Retrieved 2020-04-06).

- Schreiber. In: Heinrich August Pierer, Julius Löbe (Pub.): Universal-Lexikon der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit. Vol. 15. Altenburg 4. Ed. 1862, p. 422f., www.zeno.org/nid/20010869697 (Retrieved 2020-04-01).

- Weech, Friedrich von: Schreiber, Alois Wilhelm. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 32 (1891), p. 471, URL: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd100400159.html#adbcontent (Retrieved 2020-04-01).

- Website Loreley Touristik e.V. URL: https://www.loreley-touristik.de/meine-loreley/sagenland-loreley/sagenland-loreley/ (Retrieved 2020-04-01).

- Website Loreley-Besucherzentrum. URL: https://www.loreley-besucherzentrum.de/loreley/ (Retrieved 2020-04-01).

- Wojcik, Paula: Klassik als kulturelle Praxis. Modellierungs- und Popularisierungsmechanismen am Beispiel der Loreley. In: KulturPoetik 18, Vol. 1 (2018), p. 51-69, URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26422519 (Retrieved 2020-04-06).

Anmerkungen:

- Website of Loreley Touristik e.V. URL: https://www.loreley-touristik.de/meine-loreley/sagenland-loreley/sagenland-loreley/ (Retrieved 2020-04-01). Zurück

- Dirsch 2016, https://wiki.staatspolitik.de/index.php?title=Loreley (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Benner 2005, http://www.sehepunkte.historicum.net/2005/06/7615.html (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Benner 2005, http://www.sehepunkte.historicum.net/2005/06/7615.html (Retrieved 2020-04-03); Philippson 1947, p. 249f., https://www.jstor.org/stable/459203 (Retrieved 2020-04-06). Zurück

- Feuerlicht 1980, p. 82, https://www.jstor.org/stable/405246 (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Leie, Lei, f. fels, stein. In: Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm (Pub.): Deutsches Wörterbuch. Vol. 12: L, M – (VI). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1885, http://woerterbuchnetz.de/cgi-bin/WBNetz/wbgui_py?sigle=DWB&lemid=GL04319 (Retrieved 2020-04-07). Zurück

- Feuerlicht 1980, p. 84, https://www.jstor.org/stable/405246 (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Kluckhohn 1955, p. 589ff., https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118515055.html#ndbcontent (Retrieved 2020-04-08). Zurück

- Feuerlicht 1980, p. 82, https://www.jstor.org/stable/405246 (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Weech 1891, p. 471, https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd100400159.html#adbcontent (Retrieved 2020-04-01); Pierer/Löbe 1862, p. 422f., http://www.zeno.org/nid/20010869697 (Retrieved 2020-04-01). Zurück

- Karst 1968, p. 38ff., www.jstor.org/stable/3529041 (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Dieterle 2001, p. 103ff., www.jstor.org/stable/40621625 (Retrieved 2020-04-02). Zurück

- Karst 1968, p. 37, www.jstor.org/stable/3529041 (Retrieved 2020-04-03); Loreley-Besucherzentrum, https://www.loreley-besucherzentrum.de/loreley/ (Retrieved 2020-04-01). Zurück

- Dieterle 2001, p. 98f., www.jstor.org/stable/40621625 (Retrieved 2020-04-02); Wojcik 2018, p. 65, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26422519 (Retrieved 2020-04-06); Kiewitz 2005, https://www.hsozkult.de/publicationreview/id/reb-6685 (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Galley 1969, p. 286ff., https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118548018.html#ndbcontent (Retrieved 2020-04-14). Zurück

- Richard A. Bermann: Heine, der Journalist. In: Der Weg. Wochenschrift für Politik und Kultur 1 (1905/06) 21, p. 13f., quote in Wojcik 2018, p. 59, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26422519 (Retrieved 2020-04-06), translation KK. Zurück

- Karst 1968, p. 37, www.jstor.org/stable/3529041 (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Wojcik 2018, p. 63, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26422519 (Retrieved 2020-04-06). Zurück

- Wojcik 2018, p. 62, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26422519 (Retrieved 2020-04-06). Zurück

- Benner 2005, http://www.sehepunkte.historicum.net/2005/06/7615.html (Retrieved 2020-04-03). Zurück

- Dieterle 2011, p. 100f., www.jstor.org/stable/40621625 (Retrieved 2020-04-02). Zurück

- Alfred John Pearson, https://drakeapedia.library.drake.edu/w/index.php?title=Alfred_John_Pearson&oldid=25076 (Retrieved 2020-04-20); Pearson 1919, p. 22, https://www.dilibri.de/rlb/content/titleinfo/181562?query=the%20rhine%20and%20its%20legend (Retrieved 2020-04-20). Zurück

- Dirsch 2016, https://wiki.staatspolitik.de/index.php?title=Loreley (Retrieved 2020-04-03); Loreley Venue Management GmbH, https://www.loreley-freilichtbuehne.de/ (Retrieved 2020-04-14). Zurück